Originally posted at MoneyGeek.com on July 8, 2024

Our research indicates some consumers are considering whether to fund a Roth IRA or permanent life insurance to plan for retirement. Why might they be making this comparison?

How much life insurance do I need? Families often ask this question when they must balance their protection against premiums. Most prospective buyers of insurance (PBOIs) weigh the probability of death with the cost. Should I self-insure or leave the coverage to an insurance company? PBOIs have asked this core question throughout my 60 years of helping them decide what to do.

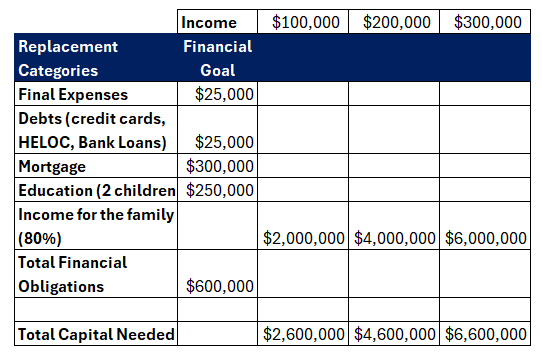

Assuming the PBOI decides to buy coverage, the next question is how much to buy and, invariably, what kind of insurance makes the most sense. For younger families, the premium cost is almost always a deciding factor. However, setting aside the discussion of term insurance versus a form of permanent insurance, the amount boils down to funds needed to cover four basic factors:

- Medical expenses and funeral costs

- Credit card and other short-term debts.

- Pay off the mortgage.

- Educational sinking fund for children

Income stability for the family determining a reasonable amount for these four categories will help the PBOI decide on the amount of coverage.

Assuming a family of four earns $100,000 a year, owns a home, and is under 40, the total insurance coverage could be $4,000,000. How did that number get determined?

Both a subjective and objective analysis help to reach the number. The objective part is just math; the subjective part relates to how much coverage the family needs based on lifestyle choices. I have heard it said that life insurance is a love gift. When someone walks out, the money walks in. Death is always shocking and usually unexpected. Families with adequate coverage can better endure the chaos and uncertainty that death brings. Families with little or no coverage face a difficult situation.

I can think of two situations that are very real and current.

- Georgia’s husband died and left her with three boys under 18 and all of the household expenses. She was a stay-at-home mom, and her loving husband left $1,500,000 in insurance. She did not pay off the house and used the $60,000 of income ($5000 a month) generated from the insurance capital to pay bills and provide schooling for her boys. Instead of a solid four-year college, they will attend a local junior college and hope to qualify for a scholarship.House payments and taxes erode 50% of Georgia’s monthly income. That leaves roughly $2500 a month for life. She is doing fine, but there is little left over for extras after auto insurance, repairs, gas, utilities, and the unexpected. Inflation makes it harder to make ends meet, leaving her only one option: spending capital. But that option reduces the income that the capital can generate. It is a downward spiral that will leave her with very little in retirement unless she can get a reasonable job. Things would have been much different if her husband had bought $3,000,000 of insurance instead of $1,500,000.

- Rose is 63 and not in good health. She usually works three days a week but cannot work more than four hours daily. When her husband passed, he left her with his IRA and social security. She owns a house with a $175,000 remaining mortgage. She inherited $400,000, which includes a $150,000 life insurance policy. A lot of money for many, but at age 63, Rose can barely make ends meet. Her total income with social security is $50,000 a year. She pays $2,000 in monthly expenses over and above the mortgage payment. She has no long-term care insurance. No retirement. She has no source of capital or income available to her. If her husband had purchased $500,000 of insurance, her prospective life in retirement would have been much better. As it stands, she can get by, but with inflation, she likely will run out of money if she lives another ten years.

The purpose of relating these stories is not to make you feel sorry for them but to point out how better planning would have helped these widows through their life circumstances. Many families do not think about buying life insurance. The extra $200-$500 a month in premium seems like a waste of money until there is no money because of death or disability.

Remember, everyone pays for life insurance. They either pay the premium costs amortized over a lifetime in small increments or pay the cost in expenses, causing deprivation and hardship because they have no money available to pay to keep a house over their heads or put food on the table. Not buying sufficient insurance has a cost that is difficult to measure and not defined until death occurs.

The Roth IRA is an excellent tool for creating wealth in retirement. However, one problem with it is the significant annual contribution limitations. A way around this limitation is to contribute to a ROTH alternative inside a retirement plan or to convert a large IRA to a ROTH by paying the taxes now instead of deferring them until retirement. Regardless of the method used to deposit money into a ROTH, having a tax-free income is appealing and drives many tax and funding decisions.

An alternative to the traditional ROTH is to use investment-grade life insurance by purchasing a policy specifically designed to reduce the cost of insurance so the cash value buildup is optimized. This strategy reduces the emphasis on insurance and allows the policy owner to grow their money inside the policy, with results similar to a ROTH.

How do a Roth IRA’s contributions and contribution limits compare to premium life insurance payments?

Think of a house purchased 20 years ago. The mortgage is much lower due to principal reductions, and the house’s value has grown with appreciation and inflation. The house owner can refinance and pull out money (sometimes significant capital) to invest and spend as appropriate. The money from the refinance is tax-free, deferring the tax until the house is sold sometime in the future. Life insurance works similarly. The buyer purchases the insurance today and deposits premiums over 20 years. The premiums accumulate in the policy’s cash value net of the insurance cost.

At the end of 20 years, it is possible that the premiums paid have doubled in value inside the policy. At this point (although 20 years is arbitrary), annual loans can be made against the policy’s values. These loans can be treated as income and have the same characteristics as ROTH distributions.

You can do the math. In both cases, the premiums and ROTH deposits are contributed from after-tax income. The growth is inside the policy, and the ROTH is not taxed until the policy is canceled. (You might never cancel the policy, thus deferring the growth until death, when it would be tax-free.) The growth in a ROTH is never taxed, even when the ROTH is fully depleted. The family inherits the residual ROTH account, which may have very little left inside it. Unlike the ROTH, life insurance has a remaining death benefit for the family.

The big math question is simple but needs to be analyzed thoroughly. Will the ROTH outperform the life insurance? There are various ways to do this analysis. Using a qualified insurance specialist to help with this study would be very beneficial. Eventually, the study should show that the outcomes are similar. However, because there is no contribution limit on an insurance policy, using the insurance product could create a more significant outcome than the ROTH.